Whole Grain Superfood

Going with the (Whole) Grain

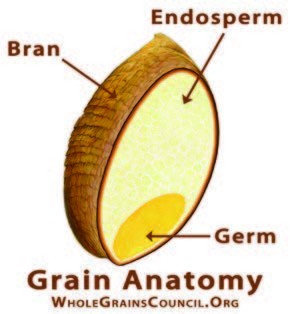

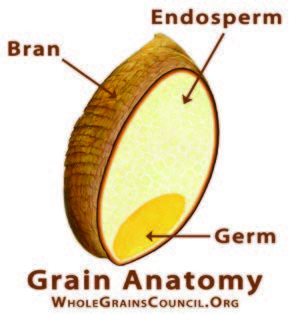

Whole Grains may be the culinary trendsetters of the 21st century, but the ancient wonders of the grain world have remain unchanged for the last several hundred years. From chia to kamut, sorghum to spelt, like many whole grains, they are significant sources of protein, fiber and other important nutrients, such as B vitamins, iron, folate, selenium, potassium and magnesium.

You may already be familiar with quinoa, which became one of the first ancient grains to trend in U.S. kitchens earlier in the decade. You’ll find more below, each a story to tell and a taste to be discovered:

Amaranth,* native to Peru and a major food crop of the ancient Incas, has a peppery taste and a versatile cooking profile – bake it with bananas, use it to coat chicken or fish or toss with vegetables for a fresh salad.

Farro goes back 10,000 years to the time of the Fertile Crescent, and is thought to have sustained the Roman army. Key to Mediterranean diets, this grain is higher in dietary fiber than quinoa and brown rice and lower in calories. Its dense, chewy texture works well in soups, risottos and is thought by some aficionados to make the best pasta.

Freekeh, frequently found in Middle Eastern and North African cuisine, has roots in ancient Egypt. A form of wheat known for its chewy texture and nutty flavor, it’s often sold cracked into smaller, quicker cooking pieces. Use in pilafs and salads, or cook into a delicious porridge.

Kamut, also known as Pharaoh grain in a nod to its discovery in ancient Egyptian tombs, is rich and buttery-tasting, ideal in breads, pancakes and salads, or in a breakfast bowl with avocado and other whole grains, such as quinoa.

Millet,* a staple of the long-lived Himalayan Hunzas, is likely to be more familiar to Americans as a birdseed ingredient, but this grain has a delicious, nutty like flavor. Cook as a hot cereal, steam and use in salads or bake in breads and cookies.

Quinoa,* cultivated by the Inca in the Andes, has become even more popular on the American table in recent years. Dozens of varieties exist, from mild-flavored white and yellow to earthier tasting red and black. Prepare as a breakfast cereal, substitute it for rice and pasta, add to soups and salads, or pop and eat like popcorn.

Sorghum,* from Asia and West Africa, is a source of protein, and can be substituted for wheat in baked goods, eaten like popcorn or cooked into porridge.

Teff,* from Ethiopia and Eritrea, is a smaller-sized, quick-cooking grain high in iron and calcium, with a sweet molasses-like flavor that can be cooked into a polenta or ground into flour to make gluten-free breads and baked goods.

*Gluten-free

Sources: Harvard Health & Whole Grains Council

The post Whole Grain Superfood appeared first on Specialdocs Consultants.